The best parts of Windows 11 are already in Windows 10. Here’s how to enable them | ZDNet

When Windows 11 was introduced in late June of 2021, many were excited by its revamped user interface — and countless PC enthusiasts rushed to download the Windows Insider Developer Channel builds of the new OS.

But, as they quickly discovered, the new OS has several new requirements for PCs to support its new hardware and virtualization-based security features. These features are critical for securing both consumer and business workloads alike from more sophisticated malware and exploit threats that are currently evolving in the wild.

Also: Windows 11: Everything you need to know

As it turns out, all of these features are already built-in to Windows 10 if you are running the 20H2 release (Windows 10 October 2020 Update). As a consumer, small business, or enterprise, you can take advantage of these if you deploy Group Policy or simply click into Windows 10’s Device Security menu to switch them on. You don’t need to wait until Windows 11’s release or buy a new PC.

The Device Security menu in Windows 10 20H2

Jason Perlow/ZDNet

Feature 1: TPM 2.0 and Secure Boot

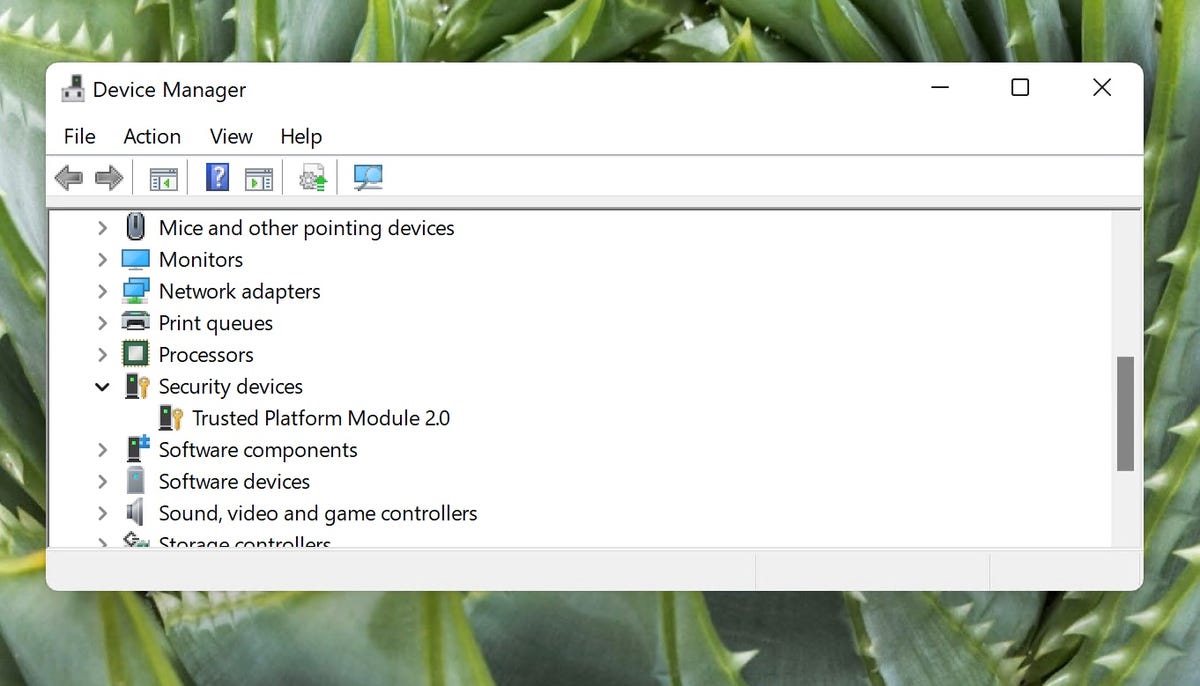

Trusted Platform Module (TPM) is a technology designed to provide hardware-based, security-related cryptographic functions. If you have a PC that was manufactured within the last five years, chances are, you have a TPM chip on your motherboard that supports version 2.0. You can determine this by opening up Device Manager and expanding “Security devices.” If it says “Trusted Platform Module 2.0,” you’re good to go.

Microsoft Windows Device Manager with TPM 2.0 Enumerated

Jason Perlow/ZDNet

This is shown as “Security Processor” in the Device Security Settings menu in Windows 10 (and Windows 11).

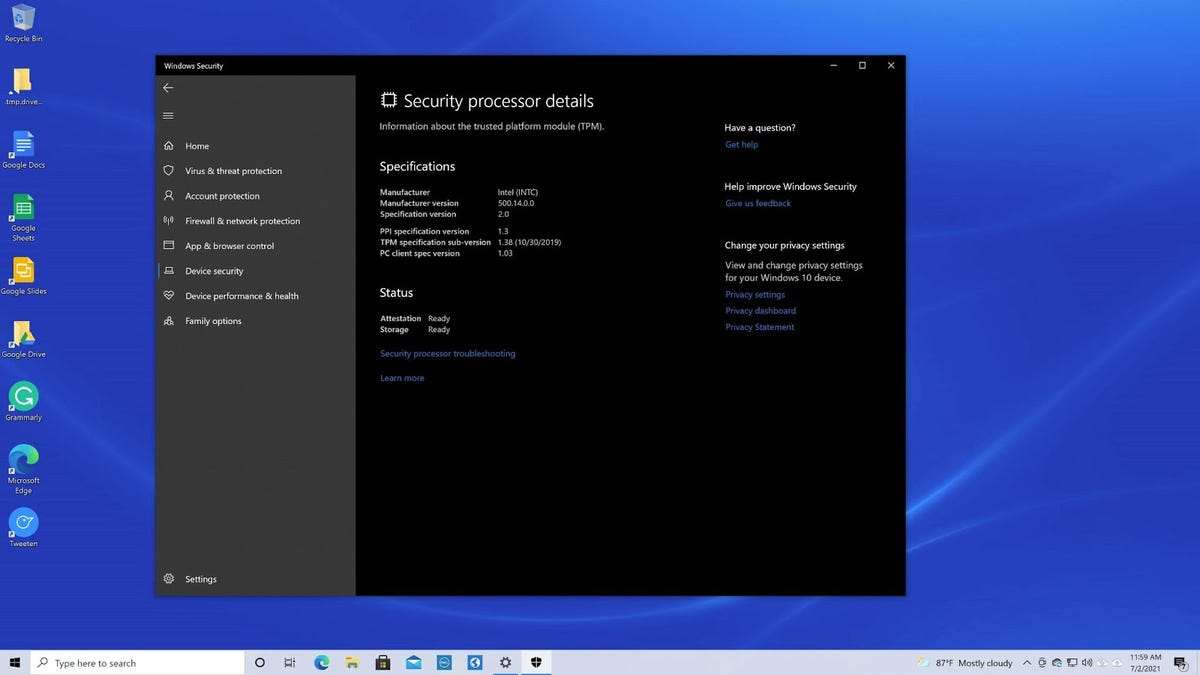

So what does TPM actually do? It is used to generate and store cryptographic keys unique to your system, including an RSA encryption key unique to your system’s TPM itself. In addition to being used traditionally with smart cards and VPNs, TPMs are used to support the Secure Boot process. It measures the integrity of the boot code of the OS, including the firmware and individual operating system components, to make sure they haven’t been compromised.

There’s nothing you need to do to make it work; it just does, provided it is not disabled in your UEFI. Your organization can choose to deploy Secure Boot on Windows 10 via Group Policy or an enterprise MDM-based solution such as Microsoft Endpoint Manager.

While most manufacturers ship their PCs with TPM turned on, some may have it disabled, so if it doesn’t show up in Device Manager or shows it as disabled, boot up into your UEFI firmware settings and look.

If the TPM has never been prepared for use on your system, simply invoke the utility by running tpm.msc from the command line.

Security Processor (TPM 2.0) details in Windows Device Security.

Feature 2: Virtualization-Based Security (VBS) and HVCI

While TPM 2.0 has been common in many PCs for as long as six years, the feature that really makes the security rubber hit the road in Windows 10 and Windows 11 is HVCI or Hypervisor-Protected Code Integrity, also referred to as Memory Integrity or Core Isolation, as it appears in the Windows Device Security menu.

While it is required by Windows 11, you need to turn it on manually in Windows 10. Simply click on “Core Isolation Details” and then turn on Memory Integrity with the toggle switch. It may take about a minute for your system to turn it on, as it needs to check every memory page in Windows before enabling it.

This feature is only usable on 64-bit CPUs with hardware-based virtualization extensions, such as Intel’s VT-X and AMD-V. While initially implemented in server-class chips as far back as 2005, they have been present in almost all desktop systems since at least 2015, or Intel Generation 6 (Skylake). However, it also requires Second Level Address Translation (SLAT), which is present in Intel’s VT-X2 with Extended Page Tables (EPT) and AMD’s Rapid Virtualization Indexing (RVI).

There’s an additional HVCI requirement that any I/O devices capable of Direct Memory Access (DMA) sit behind an IOMMU (Input-Output Memory Management Unit). Those are implemented in processors that support Intel VT-D, or AMD-Vi instructions.

It sounds like a long list of requirements, but the bottom line is that you are good to go if Device Security says these features are present in your system.

Windows 10 Device Security Core Isolation (Memory Integrity) Feature

Jason Perlow/ZDNet

Isn’t virtualization mainly used to improve workload density in datacenter servers or by software developers to isolate their testing setup on their desktops or run foreign OSes such as Linux? Yes, but virtualization and containerization/sandboxing are now increasingly used to provide additional security layers in modern operating systems, including Windows.

In Windows 10 and Windows 11, VBS, or Virtualization-based Security, uses Microsoft’s Hyper-V to create and isolate a secure memory region from the OS. This protected region is used to run several security solutions that can protect legacy vulnerabilities in the operating system (such as from unmodernized application code) and stop exploits that attempt to defeat those protections.

HVCI uses VBS to strengthen code integrity policy enforcement by checking all kernel-mode drivers and binaries before starting and preventing unsigned drivers and system files from being loaded into system memory. These restrictions protect vital OS resources and security assets such as user credentials — so even if malware gets access to the kernel, the extent of an exploit can be limited and contained because the hypervisor can prevent the malware from executing code or accessing secrets.

VBS performs similar functions for application code as well — it checks apps before they are loaded and only starts them if they are from approved code signers, doing this by assigning permissions across every page of system memory. All of this is performed in a secure memory region, which provides more robust protections against kernel viruses and malware.

Think of VBS as Windows’ new code enforcement officer, your kernel and app Robocop that lives in a protected memory box that is enabled by your virtualization-enabled CPU.

Feature 3: Microsoft Defender Application Guard (MDAG)

One particular feature that many Windows users are not familiar with is Microsoft Defender Application Guard, or (MDAG).

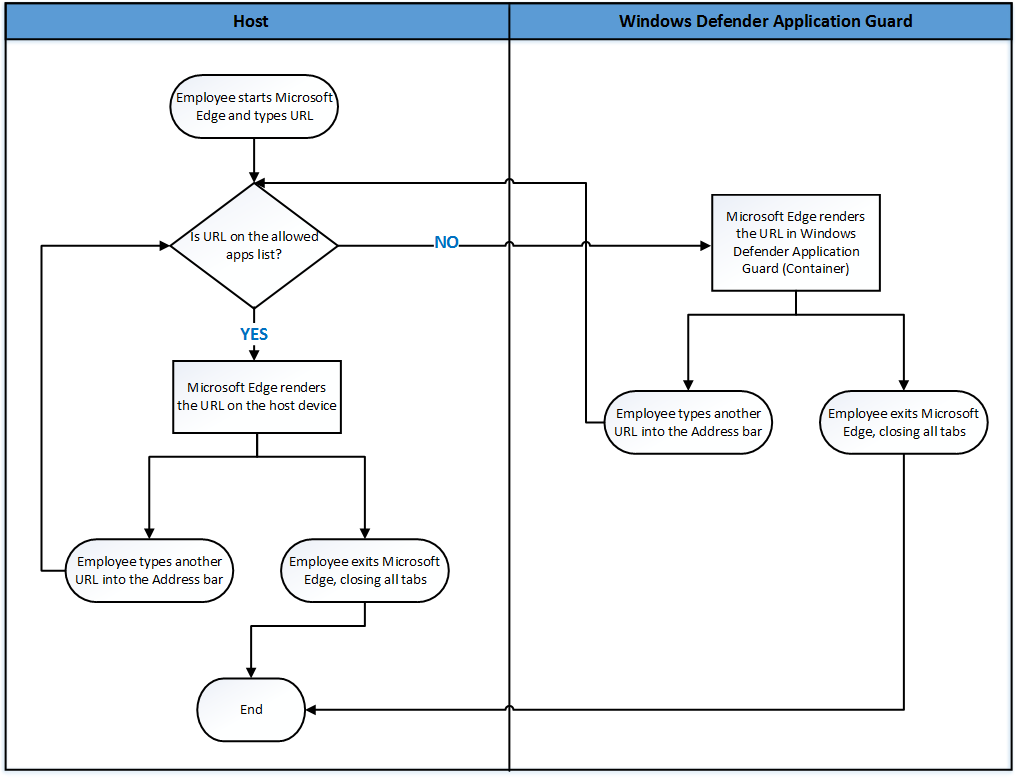

This is another virtualization-based technology (also known as “Krypton” Hyper-V containers) that, when combined with the latest Microsoft Edge (and current versions of Chrome and Firefox using an extension), creates an isolated memory instance of your browser, preventing your system and your enterprise data from being compromised by untrusted websites.

Windows Defender Application Guard in use on Microsoft Edge

Jason Perlow/ZDNet

Should the browser become infected by scripting or malware attacks, the Hyper-V container, which runs separately from the host operating system, is kept isolated from your critical systems processes and your enterprise data.

MDAG is combined with Network Isolation settings configured for your environment to define your private network boundaries as defined by your enterprise’s Group Policy.

How MDAG works on the host PC and the isolated Hyper-V browser container. (Source: Microsoft)

Microsoft

In addition to protecting your browser sessions, MDAG can also be used with Microsoft 365 and Office to prevent Word, PowerPoint, and Excel files from accessing trusted resources such as enterprise credentials and data. This feature was released as part of a Public Preview in August of 2020 for Microsoft 365 E5 customers.

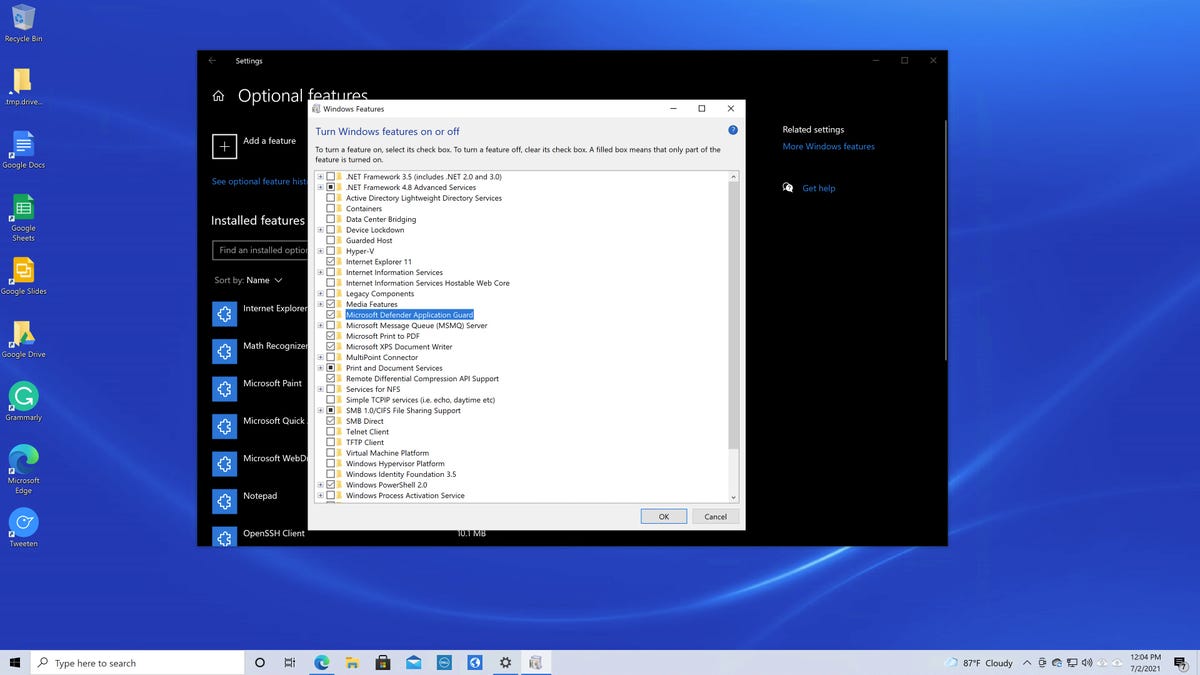

MDAG, which is part of Windows 10 Professional, Enterprise, and Educational SKUs, is enabled with the Windows Features menu or a simple PowerShell command; it doesn’t require Hyper-V to be turned on.

Microsoft Defender Access Guard in the Turn Windows Features On or Off Menu.

Jason Perlow/ZDNet

While MDAG primarily targets enterprises, end-users and small businesses can turn it on with a simple script that sets the Group Policy Objects. This excellent video and accompanying article published at URTech.Ca covers the process in greater detail.

For all the latest Technology News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.