Cybersecurity has a desperate skills crisis: Rural American could have the answer | ZDNet

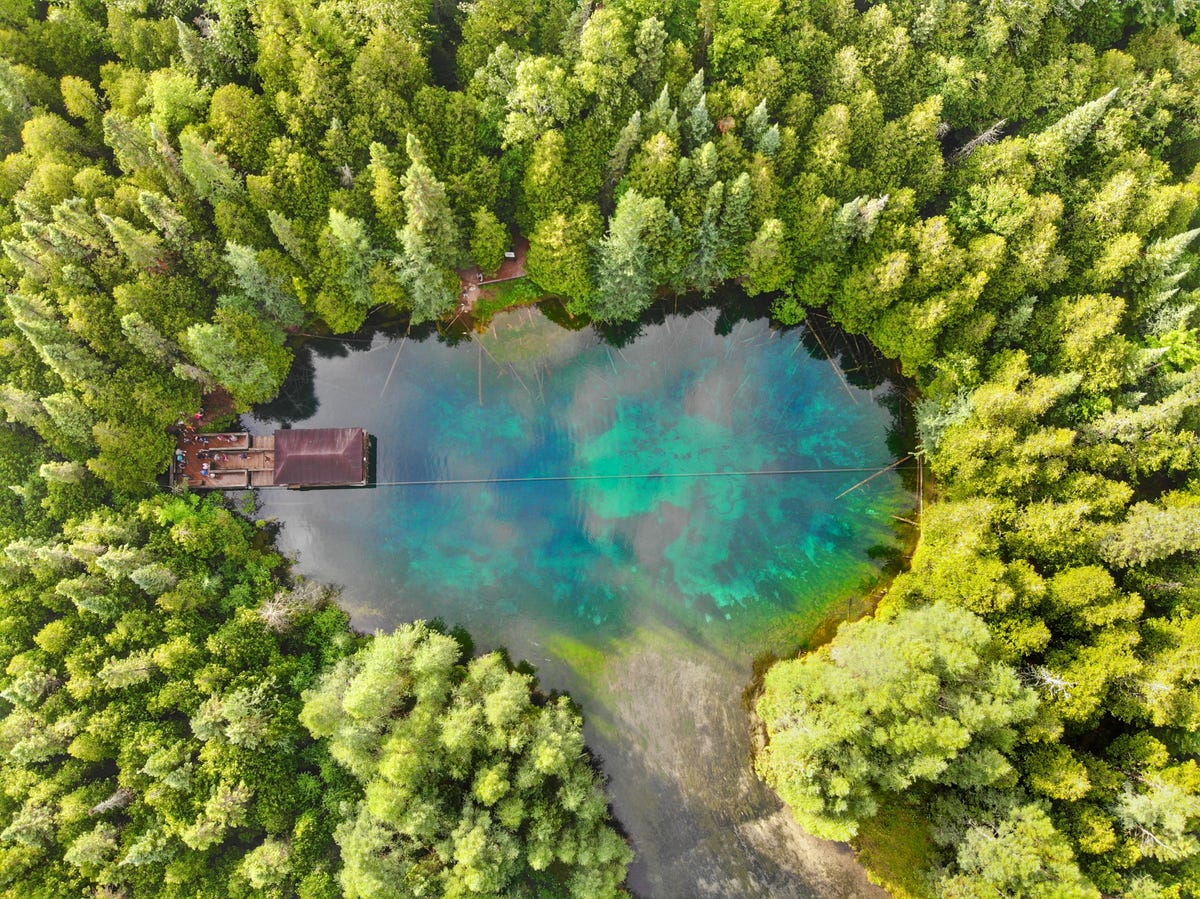

Image: Chris Pagan/Discover Manistique

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan is home to 30% of the county’s landmass, but just 3% of its population.

Boasting dense technicolour forests dotted with waterfalls and surrounded by dazzling turquoise lakes, the Upper Peninsula (UP) lures explorers and lovers of the outdoors and is a world away from the noisy, kinetic streets of the Michigan capital of Detroit some 450 miles away.

When J.R. Cunningham arrived in the tiny rural town of Manistique in UP 13 years ago, it soon became apparent that he was something of a novelty in a town in which most of the workforce is employed in retail, manufacturing and the service industry.

“When I got to Manistique, what I quickly realised was there were no IT people there – like, none,” Cunningham tells ZDNet.

“If you think about it, really the profession hadn’t existed. We didn’t even start using the term ‘cybersecurity’ until about 10 years ago. Before then we called it information security.”

Cunningham has been working in cybersecurity for 25 years. Now the chief security officer (CSO) of managed security service provider Nuspire, Cunningham has spent much of his career trying to spread awareness of the cybersecurity profession and the opportunities it presents to young people.

Downtown Manistique, MI.

Image: Discover Manistique

“When I started in the profession you could kind of hold the whole thing in the palm of your hand,” he says.

“Today, if you say I want to be a cybersecurity practitioner, it’s really such a multifaceted career that you kind of have to match the part of the profession with what tickles your fancy and where your interests lie.”

Cunningham moved to Manistique, MI with his family in 2009. His wife, an occupational therapist, specialises in small communities and children, meaning the town was “a natural fit”

As the new curiosity in a town of fewer than 3,000 residents, Cunningham soon found himself being approached by people who were interested in what he did.

“I can’t tell you how many people have sat at my dinner table and asked questions about the profession and then went on to, if not be a cybersecurity professional, at least go to school and get into IT,” he says.

SEE: There’s a critical shortage of women in cybersecurity, and we need to do something about it

One of those kids was Josh Hentschell. Now senior security solutions engineer for Little Caesars Pizza in the Metro Detroit area, Hentschell discovered his passion for cybersecurity after being invited to shadow Cunningham when he was 16.

“Growing up in Manistique in a very small town, there was really only one cybersecurity professional there, and that was J.R.,” Hentschell tells ZDNet.

“He would set up client meetings and I would participate in the meetings. I wouldn’t say anything, I was just sitting there as a bystander, but it was really cool to watch him and get a feeling of how those things are done at that age.”

Josh Hentschell, senior security solutions engineer at Little Caesars Pizza.

Image: Josh Hentschell

Hentschell’s interest in cybersecurity blossomed from there. By the time he reached college age, Eastern Michigan University had launched an accredited information assurance degree – one of the first schools in the state to launch a dedicated cybersecurity programme – which Hentschell was referred to by one of his professors.

“I started my freshman year in just a basic computer programming class,” he explains. “I did that for a year, but I still really wanted to do cybersecurity.

“And so I basically packed up my bags and I moved downstate and I transferred to Eastern Michigan University, and then I went on and got my bachelor’s degree.”

Without the mentoring he received from Cunningham, Hentschell is convinced he would never have discovered a path into cybersecurity. It’s a reflection of both the challenges and opportunities faced by communities that want to attract high-paying jobs but don’t always have access to the networks – or a resident CSO – to help make it happen.

“In the State of Michigan alone, there are 7,000 to 8,0000 unfilled cybersecurity jobs,” says Doug Miller, who runs the Upper Peninsula Cybersecurity Institute (UPCI) at MNU.

SEE: Remote-working jobs: These are the highest paying tech and management roles

The university provides certification training to students through academic partnerships via Cisco, CompTIA and the EC-Council, and engages with high school and middle school students to help provide pathways into cybersecurity careers.

In January 2022, the UPCI was designated a Center of Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity (CAE-C) by the US National Security Agency (NSA).

“I’m convinced that there are people out in those rural populations that can help us solve that problem, and fill those jobs, if we can provide the opportunities for education and training to them,” he says.

Doug Miller runs the UPCI at Northern Michigan University.

Image: UPCI

Employers face a severe shortage of qualified IT and tech staff as companies increase their investments in digital innovation and shift on-premises infrastructure to the cloud.

Yet organizations have traditionally focused their hiring efforts on the area in which their offices are located – typically major towns and cities – which limits their own recruitment efforts while also severely limiting employment opportunities for anyone who lives outside of metro areas.

“Part of the challenge with the rural population is that we are a resource extraction-focused economy up here,” says Miller. “One of the only zinc mines in the United States is right down the road [and] we’re heavily invested in logging.”

Miller stresses that there is nothing wrong with these jobs: on the contrary, they’re critical to the economy and are very much needed, “especially given the price of lumbar nowadays.”

“But there are other opportunities – not everyone wants to be a logger; not everyone wants to work in the mine,” he adds. “There are other jobs that are out there that are available.”

Country life, city wage

At the same that remote working has encouraged tech companies to look beyond the walls of major cities for talent, it’s also made it possible for people to get jobs in the IT industry without being forced to relocate.

That’s a huge selling point for people who want to be part of the tech world without giving up their rural lifestyle, says Miller: “It’s a lifestyle out here of being outdoors – being able to ski and fish and mountain bike five minutes from your house.”

Doug Miller is convinced people can enjoy a rural lifestyle while earning a big city wage, thanks to improved connectivity and remote hiring.

Image: Discover Manistique

Two of the biggest challenges for the region have been internet connectivity and the geographical dispersion of the population.

Miller points out that rural economies don’t benefit from the same economies of scale as more populated regions. So, if there are only two students who want to take a cybersecurity class, it doesn’t make financial sense to hire a teacher to teach the subject.

Remote learning, therefore, enables more students to participate in courses when they might not otherwise be able to, Miller adds. Back in 2017, MNU started an initiative called the Education Access Network, an internet service provided by Northern Michigan University that enables broadband access to educational resources across the Upper Peninsula. To date, the network has served more than 16,000 households spanning some 87 rural communities.

In some of UPCI’s most recent cybersecurity courses, none of the students have been physically present, says Miller, and have instead been connecting in from “90, 100 miles away on the other side of the Peninsula.”

“That ability to reach out and hold those classes virtually has been key in being able to reach those populations,” he adds.

SEE: Cybersecurity training isn’t working. And hacking attacks are only getting worse

Reaching those populations could also enable tech companies to connect with talent they would have otherwise missed. With more companies looking at upskilling as a means to fill talent gaps, organizations are more accepting of candidates with less traditional tech backgrounds who can demonstrate transferrable core skills.

Another major challenge facing cybersecurity is an apparent lack of interest – or at least, awareness – around the nature of the industry, and what a career in the cybersecurity professional can offer.

This problem isn’t just limited to tech: research suggests that in the UK, fewer students are opting to take IT subjects at school and appear pessimistic or otherwise unsure of their capability to match the needs of employers in tech careers.

A key part of this challenge comes down to messaging: educators and employers simply have to do a better job of demystifying the cybersecurity landscape and enabling students to engage with technology at a younger age.

“One of the things we try to reinforce every time we’re with students in classes is that you do not have to be a technical expert,” says Miller who, as part of a UPCI initiative, is working with five school districts in Hooton, Michigan on a year-long planning effort for computer science and cybersecurity initiatives.

Encouraging young people to take up cybersecurity careers is critical to solving skills shortages and getting more adults into skilled, well-paying jobs.

Image: UPCI

“Cybersecurity is a team sport,” he adds. “You need people that can programme; you need people that can solve problems; you need people that can communicate; you need people that have a lot of other skills besides the very technical ones and zeroes of trying to capture packets, or write some malicious code, or defend against malicious code.”

Of course, a lack of teacher training is also an issue, particularly in more rural populations – again, looping back to the issue of economies of scale.

Miller says that, while the schools UPCI is working with are committed to figuring out a way to bring cybersecurity courses into their schools, many simply don’t have the staffing resources to do so. “The struggle is that the teachers themselves have not been trained in a lot of these concepts,” he adds.

Miller says the eventual goal is to ensure staff who are teaching cybersecurity courses are either certified or trained to more capacity: “We’re putting them through some of our certification courses, [and] we’re working with them on activities they can do with their students to help bridge that gap.”

A life’s work

In any case, it’s clear that educators and employers need to radically rethink how they engage with young people, and particularly those living in rural areas, if they hope to make any sort of meaningful progress in bridging the skills gap in cybersecurity, and tech more widely.

Cunningham is convinced that the appetite is there – but the messaging needs to evolve first. “What I’ve come to learn is that there is so much talent that’s sitting out in rural North America,” he tells ZDNet.

J.R. Cunningham, CSO at Nuspire.

Image: Nuspire

“The tech companies have not done justice to either the IT or security fields because they’ve gotten the reputation of, ‘they grind you into the dirt until you quit’. I don’t view it that way, I view it as a vocation. It’s a life’s work. It’s something that you actually wake up in the morning and put the badge on and go do your thing, and when you go to bed at night you feel pretty good that you made a difference in the world.”

Hentschell agrees: “I would say that the cybersecurity field is a very challenging field, but also very rewarding. It’s also constantly changing, something that we need to keep up on, so you’re constantly learning new things every day,” he says.

“There are so many cybersecurity jobs out there now that are unfulfilled. To me, if you’re really interested in the work, it doesn’t matter where you come from – you can do whatever you want to do, in whatever you set your mind to.”

For all the latest Technology News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.